Translated By Mohamed SAKHRI

Recently deprogrammed by France Télévisions, “Algérie, sections armes spéciales” sheds light on the chemical warfare conducted by the French army against the civilian population. By giving a voice to victims and former combatants, the documentary also raises questions about the transparency of military archives and collective memory.

Colonization and the Algerian War remain sensitive subjects, as demonstrated by the recent controversy surrounding Jean-Michel Aphatie, who faced criticism for comparing the crimes committed by the French army during the colonization of Algeria to Oradour-sur-Glane. The last-minute deprogramming of the documentary film “Algérie, sections armes spéciales” by France Télévisions also attests to this. While the true reasons for this decision are unknown, beyond the soberly mentioned current events in the official statement from the public service television, there is no doubt that it illustrates the pressure of the prevailing Algerophobia, amplified, among others, by the Minister of the Interior.

The film’s producer, Luc Martin-Gousset (Solent production), wants to emphasize that “France Télévisions, by financing the film, allowed Claire Billet to conduct her investigation and demonstrate unambiguously that if the French army does not want to open its archives on this period, it is out of fear that they may contain elements that could incriminate it for war crimes in Algeria.”

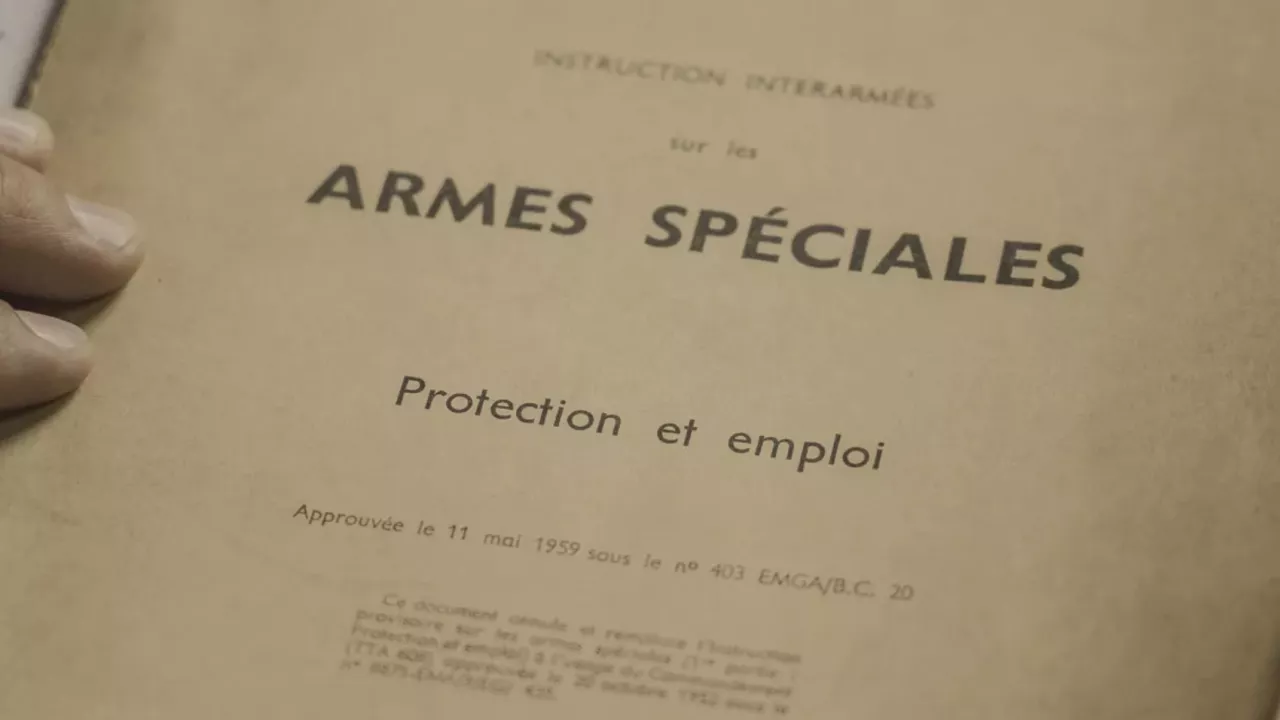

Indeed, with this film – available on the France Télévisions platform – a shameful chapter of the Algerian War is brought to the attention of the general public. Drawing on archives and testimonies from both sides, director Claire Billet recounts the regular use of chemical weapons by the French army, in violation of the Geneva Protocol that prohibited their use. The film relies, in particular, on the persistent work of a historian, Christophe Lafaye, around a question that remains problematic, sixty years after the end of the war, for the military world.

In 1925, France had been the first of the 135 nations to sign the Geneva Protocol, the day after the “Great War” (1914-1918) that had introduced the use of toxic gases and its sinister consequences; it had left many unused stocks. It is precisely from these stocks that the French army drew, four decades later, what would become the arsenal of the special weapons sections dedicated to the “war of the caves.”

In “The First Algerian War. A History of Conquest and Resistance (1830-1852)” (la Découverte), historian Alain Ruscio explains:

The caves were used as places of refuge. In 1844-45, during the conquest of Algeria, “enfumades” were carried out by the infernal columns of General Bugeaud, and an entire tribe was gassed in the Dahra massif. It was a perfectly assumed strategy aimed at subjugating populations through massacres and terror. During the war of independence, the use of chemical weapons responded more to a tactical logic: to assault underground shelters and prevent their reuse.

Several documents unearthed by Christophe Lafaye, a researcher specializing in military history, describe how the political decision was made in March 1956, as evidenced by a letter from the superior inter-armed forces commander of the 10th military region (which covers Algeria) to the Secretary of State for the Armed Forces Land, titled: “Use of chemical means”: “The colonel of special weapons visited me. He informed me that he had obtained your principle agreement regarding the use of chemical means in Algeria.”

Kill their occupants and make the caves unusable In September 1956, the minutes of a meeting at the Army General Staff mention “a study of the general policy of using chemical weapons in Algeria.” Objective: to infect the caves where the insurgents (referred to in contemporary documents as “outlaws”) take refuge, to take prisoners or kill their occupants, and to make them unusable.

From then on, the army organizes itself methodically. It conducts tests to determine “the product to be used in each specific case,” the operating procedures, and the personnel who will be dedicated to these missions: a special weapons battery (BAS) is created in December 1956. A hundred sections will be distributed throughout Algerian territory by General Raoul Salan. The Challe plan will revise this organization in 1959 to make it more effective. The gas used is CN2D, packaged in grenades, candles, and rockets: a derivative of arsenic (Adamsite or DM) combined with chloroacetophenone (CN), which is highly toxic.

Christophe Lafaye, a doctor in contemporary history and a specialist in military history, is completing a research habilitation thesis at the University of Burgundy on the use of chemical weapons in Algeria, after defending a thesis on France’s engagement in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2012. He explains to Orient XXI:

“This research project was born in 2011 when I attended a training session for soldiers preparing to intervene in underground environments in Afghanistan, drawing on the experience gained from the Algerian War. That’s how I discovered the existence of these special weapons units.”

Shame and anger of former combatants From one lead to another, he found several former combatants who opened their personal archives to him. “Five thousand men passed through these cave sections. Very few of them spoke to their children about it,” he says.

The film shows some of them, flipping through black and white photo albums or rereading documents from the time. Yves Cargnino, from a military family, who suffers from respiratory insufficiency due to his exposure to the gases, had to fight for fifteen years against the Ministry of Defense to have his injury recognized. In memory of his fallen comrades, he gives in to a gesture of anger and despair.

Armand Casanova, who enlisted at the age of 18, was nicknamed “the Rat.” Being small in stature, he was one of the first to enter the underground passages. “I can still smell the gas. And the smell of death too.” He participated in two to three operations per month during his two and a half years of mobilization in Algeria.

Jacques Huré served only nine months in the special weapons battery. He sighs, lost in his memories: “We knew there were things that were prohibited by the Geneva Convention, but we didn’t know which gases. They didn’t explain anything to us!”

Jean Vidalenc, ten months in the cave section in the Aurès massif: “The first time we used these gases, we ended up with burns all over where we were sweating. We protested, and they provided us with sealed suits. I never knew what it was.”

Claire Billet also films the opposing camp. She meets Algerian survivors of the Ghar Ouchettouh cave in the Aurès, which was gassed on March 22, 1959, with nearly 150 villagers inside. Seeking refuge in the cave to escape the operations of the French army, which had declared the region a prohibited zone, the inhabitants had no chance. Only six young men, now elderly gentlemen, survived.

Mohamed Ben Slimane Laabaci was 12 years old: “I came back the next day with my mother. We saw them taking out the bodies. You couldn’t recognize them. They were all blue (…) the bodies were all swollen.” Amar Aggoun, 15 years old at the time of the attack: “They [the French soldiers] let us go and then withdrew. When we reached 500 meters, they blew up the cave.”

Bodies trapped in collapsed caves Bodies remained inside under the collapsed rock piles. The war memorial honors 118 bodies found at independence and buried in the village cemetery. For the French army, which had published a statement on May 6, 1959: “This operation made it possible to put 32 rebels out of action (…) [and] to free 40 young Muslims that the rebels were holding prisoner in a cave.”

On May 14 of the same year, Ferhat Abbas protested against these events in a telegram to the Red Cross:

“I allow myself to denounce (…) [the] reprisals of the French army against the civilian population in Algeria. Recently, in the douar Terchioui near Batna, a hundred people, many of them women and children, took refuge in a cave to escape the sweep. All of them perished, asphyxiated by gas.”

According to Christophe Lafaye, between 8,000 and 10,000 gas attacks were carried out throughout the war. The historian has documented 440 of them, which he has plotted on a map. A complete inventory remains to be done.

The task will not be easy. Because while several accounts of the use of chemical weapons have been published since the 1960s, with little dissemination, French military archives have only been opened for a short time. Christophe Lafaye explains:

“The archives were quite widely opened between 2012 and 2019. But at the end of 2019, a major upheaval occurred: the contemporary archives of the Ministry of Defense were closed due to a legal conflict between two texts.

The 2008 law on archives declassified defense archives after fifty years, but the Ministry of the Armed Forces opposed it with a general inter-ministerial instruction from the General Secretariat for Defense and National Security, ordering declassification on a document-by-document basis. This procedure required a lot of archivists and a lot of time.

Archivists and historians filed appeals before the Council of State, which ruled in their favor in June 2021. But the Ministry of the Armed Forces counterattacked and took new measures that further complicate the situation, creating archives without a communication delay.

When I returned in 2021, my requests for access to documents that I had been able to consult before were systematically denied, citing Article L-213, II of the 2008 law on incommunicable archives.”

Protect the reputation of the French army at all costs Under this article, certain archives are incommunicable on the grounds that they could enable the design, manufacture, use, and location of weapons of mass destruction. “Now, they are closing operational journals, operation reports, and unit creation minutes on me, citing this article. In fact, the Ministry of the Armed Forces wants to protect its reputation during the Algerian War,” the historian laments.

Because the subject remains sensitive. Christophe Lafaye discovered this the hard way:

“My work on Afghanistan was awarded the military history prize of the Ministry of the Armed Forces in 2014, but when I made it known that I was working on the Algerian War on a sensitive subject, I was made to understand that I had, in a way, switched sides. The Algerian War is still a problem.

The lock is powerful. Since 2015, we have been living in a society dominated by the fear of terrorism, which pushes for restrictions on freedoms. There are also sociological reasons: some senior officers come from military families generation after generation. The archives tell part of the family stories, and the fear of scandal persists, despite four amnesty laws. However, the objective of historians is not to index individuals. In fact, we anonymize living witnesses who wish it.

What interests us is rather understanding how the political decision was made, how it was implemented, and its consequences. On this point, what has most intrigued me from a historical perspective is that the two people at the heart of the decision to use chemical weapons in 1956, Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury, the Minister of Defense, and General Charles Ailleret, the commander of the special weapons staff, were two former great resistance fighters, and even – for Ailleret – a former deportee. And yet, they seem to have no qualms about it.”

After 1962, at B2 Namous in the Sahara desert, France continued, with the agreement of independent Algeria, nuclear, chemical, and biological tests. Algiers demands the decontamination of the site promised by François Hollande. But in the context of tension between France and Algeria, which seem to endlessly replay the war of independence, no progress in memory or reconciliation is on the horizon.

References

Billet Claire, « Algérie, la guerre des grottes », Revue XXI, tome 58, avril 2022, p. 48-64.

Decision to use chemical weapons in the 10th military region, box GGA 3R 347-348 of the National Overseas Archives (ANOM), consulted in July 2023.

General study on the use of special weapons in Algeria, box 15T582 of the Historical Defense Service in Vincennes (partially accessible following the decision of the Commission for Access to Administrative Documents [CADA] in December 2021). This important document was exceptionally disclosed in 2006 to the German researcher Fabian Klöse and widely cited in his 2013 book.

Klose, Fabian, Human Rights in the Shadow of Colonial Violence: The Wars of Independence in Kenya and Algeria, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2013.

Christophe Lafaye, « La guerre souterraine et l’usage des armes chimiques en Algérie (1954-1962) », In. Pr. Renaud Meltz (sous dir.), Histoire des mensonges d’État sous la Ve République, Nouveau Monde Éditions, 2023, p 166-174.

Article 23 of Law No. 2021-998 of July 30, 2021, relating to the prevention of acts of terrorism and intelligence, amends Article L. 854-9 of the Internal Security Code. This amendment concerns provisions related to intelligence.

Lafaye Christophe, « L’obstruction d’accès aux archives du ministère des armées. Les tabous du chimique et de la guerre d’Algérie », in Renaud Meltz (dir.), Histoire des mensonges d’État sous la Ve République, Paris, Nouveau Monde Éditions, 2023, p 83-89

Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury served as Minister of Defense from May 1, 1956, to May 21, 1957. He oversaw the experimentation and implementation phase of chemical warfare in Algeria before assuming the position of President of the Council.

Subscribe to our email newsletter to get the latest posts delivered right to your email.

Comments